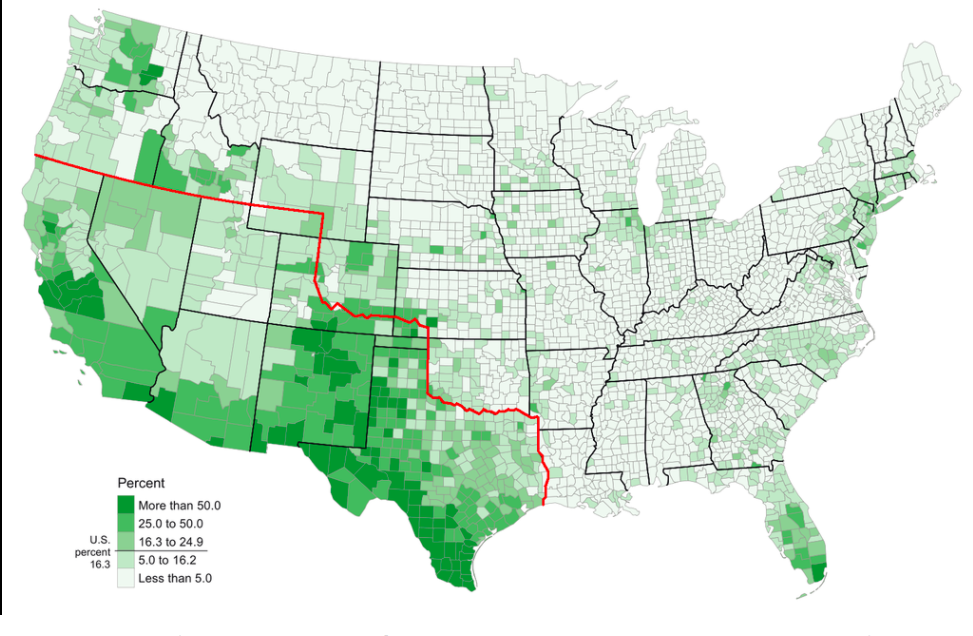

This year, on the 4th of July, I find myself more pensive than usual about who we are, or are becoming as a nation. A friend of mine recently posted an offer to procure T-shirts she has found in Mexico for her American friends, which say “Make America Mexico Again” with a map. Funny. Sad. I feel sad for all of us, this year. And especially sad for California’s Mexican population, who really were here first, and whose land we have stolen and many of whom, along with our other immigrant neighbors, live in fear throughout my state.

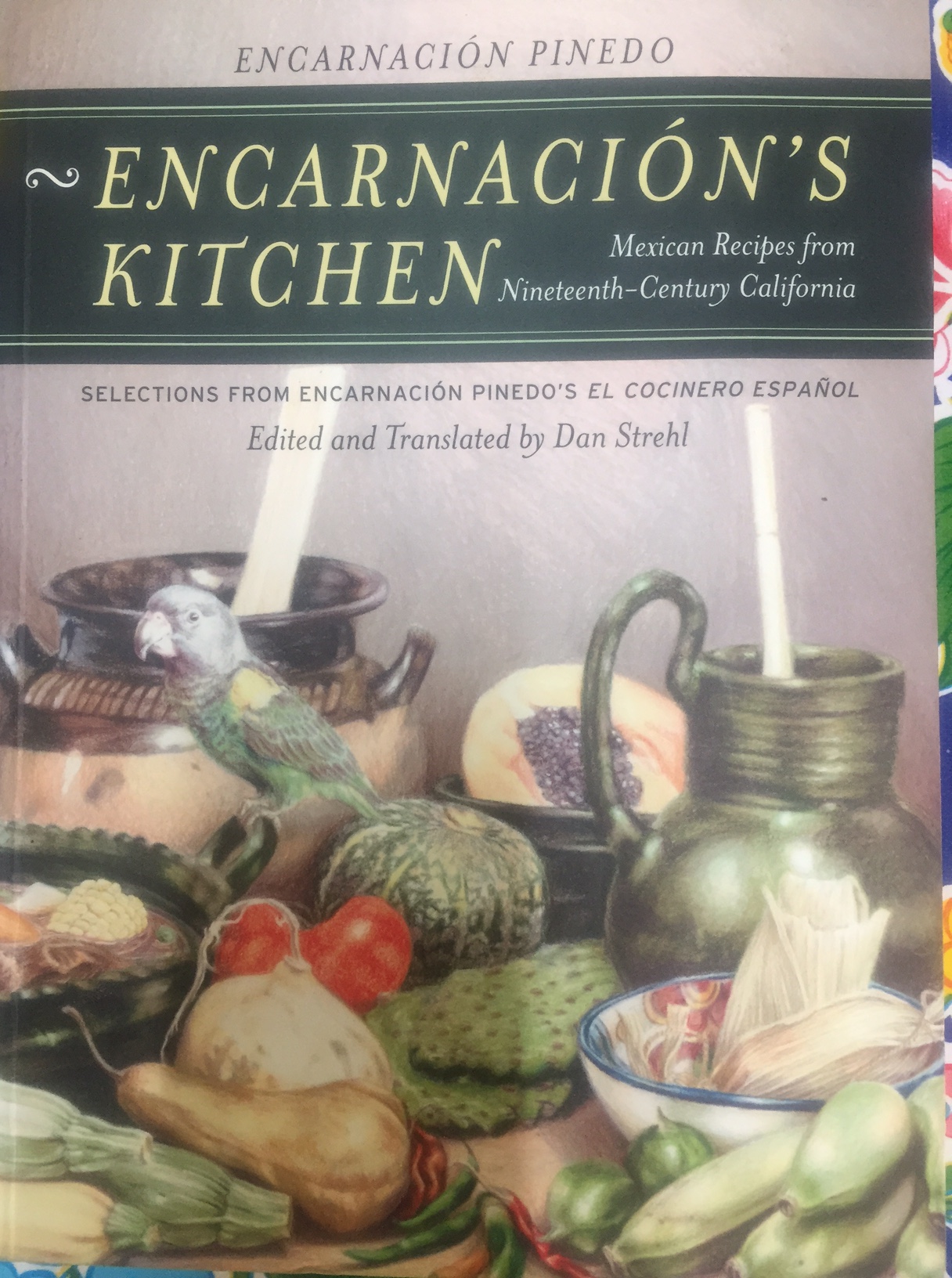

This is going through my head, as I get ready to cook for the 4th of July, the menu a cross between Modern Mexican fare and California Cuisine. Prepping through this stream of consciousness, somehow I come to Encarnación Pinedo. She really does embody this intersection between food and politics, between immigrant and citizen, between “Old California cuisine” as described by Barbara Hansen in her 2004 review of the Encarnación’s Kitchen, Mexican Recipes from Nineteenth-Century California (edited and translated by Dan Strehl); and new, as the book is credited with, “documenting the start of California’s love affair with fruits and vegetables, fresh edible flowers and herbs, aggressive spicing, and grilling over native wooden fires”(Reichl). For me, introducing her to those of you who are unfamiliar with her body of work somehow seems fitting on this particular 4th of July in California.

Described as the Julia Child of her era, Pinedo’s landmark cookbook, El Cocinero Español, was published in Spanish in 1898 and is credited with being the first written by a Latina in California. Pinedo, herself, described the work as much more than a cookbook, as an “act of creating a culinary legacy for succeeding generations thus express[ing] self-love in the face of denigration, and faith in the possibility of some day reestablishing a lost cultural continuity.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and poet, Victor Valle, in his introduction to Encarnación’s Kitchen, goes a step further, saying that

“Scholars from various disciplines have now begun to read … cookbooks as literary texts rich in cultural meaning. Pinedo’s is simultaneously a book of recipes and identities… recipes [that] can best be read as testaments of hunger. She hungered for culinary and cultural continuity in a time of … violent… upheaval”.

Both statements reflect the degree to which Encarnación Pinedo could not escape the politics of her time, politics that had a direct impact on her family, social status and, ultimately, her work. The Pinedo family were influential Californio landowners who lost their holdings as a result, among other things, of the US-Mexican War of 1846-1848, as did so many early Californio families. By the end of the war, mestizo, or “mixed” families with Mexican roots found it “difficult to negotiate a favorable status” as “difference in skin color superseded all other distinctions.” (Lisbeth Haas). The Californios, as Pinedo’s family identified themselves, looked to distance themselves from their Mexican heritage in an effort to secure their place in California society of the turn of the 20th century, where, “among the racially mixed population of settlers, culture, religion, wealth, counted more than skin color as social descriptors”. Cuisine, it seems, could be counted among these.

The tendency toward Hispanic, rather than Mexican titles for her recipes may have reflected this difficulty or been designed to promote sales, or both. Her own cuisine, and even the very title of her book, El cocinero español (note the lack of reference to Mexico) “betrays the author’s desires… to bring aspects of her past to the foreground, ball pushing others to the background.” (Victor Valle).

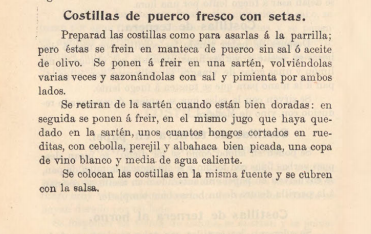

Pinedo’s struggles, both with the politics of the time and with identity come, through in her recipes, which embrace, Mexican, Hispanic and European cooking to the detriment of the English (or Gringos, whom she called “bloodless” and whom had been instrumental in displacing her family), and whose cuisine she called “the most insipid and tasteless that one can imagine.” And so, Pinedo’s recipes tend to focus on European ingredients and techniques as well Mexican ones, her cooking reflecting the balancing act that must have been her life, between two worlds. Dan Strehl, who translated the original work, describes it as containing “a more elevated and thoroughly thought-out cuisine than people would assume.” None other than Ruth Reichl was the first to publish one of Pinedo’s recipes in an article on California cuisine for the Los Angeles Times in 1991, and called Pinedo “a remarkably sophisticated cook” and going on to note that “In addition to recipes we would think of as Spanish– salt cod in tomato, and Mexican –.[steamed tamales which, in the book, Pinedo refers to as ‘ultima novded’ or ‘the latest thing’]; stuffed chiles with walnut sauce, her book offers recipes using truffles and pate de foie gras. And yet the bulk of her recipes are simple, sophisticated–and perfect for modern life.” The Times went on to print a recipe for Costillas de Puerco Fresco con(Fresh Pork Chops With Mushrooms), Reichl adding this interesting note at the end, “because pork is now a lot leaner than it was at the turn of the century, it’s likely that you will have few drippings left in skillet after the chops are seared. We added 1 tablespoon olive oil in place of the drippings. You may also want to add an additional 1 tablespoon olive oil before searing the chops”.

Pinedo’s recipes are descriptive, as was the style of cookbooks of the time, with no list of ingredients nor reference to measurements. The recipe printed in the LA Times in 1991 did include an ingredients list and measurements; I can only imagine that these were the result of work in the Times’ test kitchen or by Ruth Reichl, herself. I have included the original Spanish, the translated version and the LA Times recipes below, for an interesting comparison.

Costillas de Puerco Fresco con Setas from Encarnación’s Kitchen, Mexican Recipes from Nineteenth-Century California

Prepare the pork chops as though they were to be roasted on the grill; but these are fried in pork fat without salt or olive oil. Fry them in a skillet, turning them several times and seasoning both sides with salt-and-pepper. Remove them from the skillet when they are golden brown. Done put some sliced mushrooms in the drippings that are left, with onions, parsley, finely chopped basil, a cup of white wine, and a half a cup of hot water. Put the chops in the same dish and cover with the sauce.

Costillas de Puerco Fresco con Setas (Fresh Pork Chops With Mushrooms) from Los Angeles Times

1 1/4 pounds pork chops (4 chops)

Salt, pepper

1/2 pound mushrooms

1 medium onion, chopped

1/4 cup minced parsley

2 tablespoons basil, minced

1 cup white wine

1/2 cup hot water

Heat non-stick skillet and sear pork chops until golden brown. Turn several times, seasoning both sides to taste with salt and pepper.

Remove chops. Reheat drippings and cook mushrooms, onion, parsley, 1 tablespoon basil, wine and hot water. Return chops to pan and cover with sauce. Cover pan and simmer until chops are tender, 35 to 45 minutes. Uncover last 15 minutes of cooking to reduce liquid. Garnish with remaining 1 tablespoon of basil. Makes 4 servings